Will the EU's disinformation rules matter?

🤥 Faked Up #37: The EU's code of conduct on disinformation is integrated into the Digital Services Act; Community Notes users ❤️ fact-checkers; and RFK Jr. is sworn in.

For any Francophone readers: I was quoted on Libé being skeptical about the promises made by many commercial deepfake detectors:

This newsletter is a ~12 minute read and includes 64 links. The DSA story was updated to add the comments and scores of two additional experts.

NEWS

X verified a crypto-pushing account impersonating the president of Malta. A Brazilian court acquitted fact-checker Tai Nalon in a libel case. Android seismometers sent out an alert for a non-existent earthquake in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Match claims 99.4% of its users' profile pictures show no sign of "concerning AI manipulations". AI-generated YouTube videos of a fake dispute among EU officials racked up half a million views. Scarlett Johansson did not love an AI-generated video depicting her and other Jewish celebrities wearing a "🖕 Kanye" T-shirt. Anti-misinfo startup Logically laid off ~40 employees. The Take It Down Act passed the US Senate (again) and heads for the House; some nonprofits expressed concerns. Ukraine's President Zelenskyy said Donald Trump lives in a "disinformation bubble." Grok AI is not smarter than humans. 250 people of 20 nationalities were released from a Myanmar scam center.

TOP STORIES

Tech platforms (minus one) signed on to the EU code of conduct on disinformation. Does it matter?

Last Thursday, the EU Commission announced "the official integration of the voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation into the framework of the Digital Services Act (DSA)." This flourish of Eurocratese may determine the boundaries of platform interventions against disinformation through the end of this decade.

The DSA already required large online platforms and search engines to share data about online harms and have appropriate countermeasures in place. It currently applies to a couple dozen websites ranging widely from Facebook, TikTok and YouTube to Pornhub, Shein and Booking. Late in 2023, the EU Commission started investigating X for being in possible violation of the DSA, kickstarting a heated exchange between US House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan and then-Commissioner for Internal Markets Thierry Breton.

Transatlantic tensions have ramped up further this year.

Opportunist-in-chief Mark Zuckerberg used his January speech denouncing fact-checking as an opportunity to sic the new administration on the EU, accusing it of passing an "ever-increasing number of laws institutionalizing censorship." In a Congressional hearing last week, Jim Jordan said he was "nervous about what's happening in Europe," where "the Digital Services Act [is being used] to censor globally" and promised further action.

This community of vision between the US tech i government continued with Vice President J.D. Vance's speech at the Munich Security Conference. Vance said the Biden administration had "threatened and bullied social media companies to censor so-called misinformation" and denounced EU "commissars" and "entrenched interests hiding behind ugly Soviet era words like misinformation." (I'm not entirely unconvinced by his concerns about the Romanian election being annulled; DSA-mandated transparency may actually help by clarifying what happened.)

Elon Musk's X did not sign on to the code, but is still bound to the DSA and is being sued in Germany for access to data required under the regulation.

Despite promising to stand up to censorship, Meta did sign up to the code, alongside other US tech giants like Google. Behind the censorship theatre, platforms recognize this is primarily a transparency mechanism. As Programme Director of the European Digital Media Observatory Paolo Cesarini told me, "no provisions in the DSA require taking down harmful but lawful content." The EU law is also a convenient tool to block more interventionist anti-misinformation legislation at the national level, as appears to have happened this week in Ireland.

The code is now the principal way that the EU will determine whether large online platforms and search engines are compliant with DSA obligations on disinformation. As EU DisinfoLab writes, "although codes of conduct are nominally voluntary, the DSA pushes that notion to its limits" because a refusal to apply to the code might be used as evidence of infringing the law.

The code contains several reasonable-sounding commitments on demonetizing disinformation, bolstering policies against impersonation and fake engagement, minimizing the "viral propagation of disinformation," investing in provenance tools, facilitating user access to fact-checking, and providing data to researchers.

The code's integration is the culmination of a process that started eight years ago (I was somewhat involved in its inception) so it's worth asking: Will something actually change in practice? I asked eight EU law and disinformation experts this question.

Several told me the main benefit of the revamped code is the message it sends: Moderating digital disinformation is still a priority for the EU.

Journalism scholar and University of Copenhagen professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen told me that the good news about the code is "that it exists, starts with an explicit and specific commitment to citizens’ fundamental rights [...] and that is has been developed by a broad range of stakeholders."

Nielsen notes that "the main actually-existing real politik alternatives on offer right now seem to be either weaponized libertarianism or greater state control with little regard for fundamental rights. Against that backdrop, the DSA and the Code of Conduct are in many ways best in class."

Ethan Shattock, a misinformation regulation expert and lecturer at Queen's University Belfast, told me that by confirming that "disinformation constitutes a systemic risk" under the DSA, the code of conduct "signals an institutional willingness" to combat the problem.

Alexandre Alaphilippe, Executive Director of EU DisinfoLab, said that "in principle," the code should help the DSA be more enforceable because "if signatories fail to uphold their commitments, it strengthens the evidence of platforms' non-compliance with the regulation."

Clara Jiménez Cruz, CEO of the Fundación Maldita.es and Chair of the European fact-checker's association also welcomed "a common agreement on what risk mitigation measures for disinformation under the DSA look like, including the fact-checking chapter." She notes this "is the most clarity and agreement we've ever had" on what will count as compliance on disinformation under the DSA.

Mariateresa Maggiolino, a data law expert and Professor at Università Bocconi in Milan, was heartened by the code's "focus on increasing transparency in political advertising," which "enhances accessibility and accountability" for spreading political disinformation.

But there's plenty missing in the code, too.

My sources worried primarily about the code being ineffective.

Jiménez Cruz says that the code of conduct's predecessor "has been in place for over three years now and most platforms have done little, if anything, to pursue the risk mitigation measures they committed to. Over the years they have either ignored, if not backtracked, on their commitments to fight disinformation."

Alaphilippe thinks "we are repeating the same cycle that has kept Brussels occupied for the past eight years" and shares the concern that the code will lack bite. He's primarily concerned that while civil society is expected to expand its monitoring efforts "there is no financial support to sustain this mission. The asymmetry of means and expectations always falls in favor of platforms, despite some of them having repeatedly failed to fulfill their commitments."

Worse, the code of conduct may prevent Member States from taking more muscular action, as we are seeing in the Irish case. Shattock says that "since 2018, several EU Member states now make the dissemination of false information online illegal" and the code "does very little to clear up the inconsistencies" between their definition and the EU's competency in the context of national elections.

Maggiolino also worries that "businesses will have to comply with a lot of regulations at once, and I’m not sure how well they’ll manage it or if the compliance will be just for show." Additionally, "users—who tend to be quick and inattentive—might not actually pay attention to disclosure signals," negating their benefit.

A couple of my sources did worry about the possible effects on freedom of speech and the interplay between economic-political interests and the code's application.

Shattock says that there are "only vague instructions on how the right to freedom of expression must be reconciled with the need for an informed electorate." He predicts that "'over-blocking' of lawful content is highly likely."

Nielsen thinks placing the primary responsibility for enforcement on the EU Commission rather than independent regulators, "is not ideal when it comes to often highly politicized issues that touch on citizens’ fundamental rights." He notes that "we have already seen a past Commissioner who seemed willing to use disinformation discussions as an opportunity for political theater." Putting the Commission in charge could also swing the other way, with "politically motivated underenforcement and watering down."

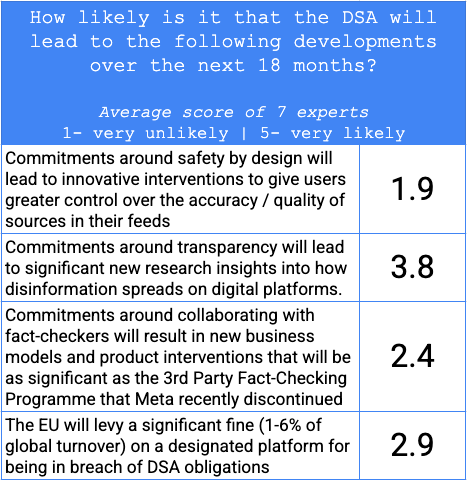

Finally, I asked my expert sources, including one who chose to remain anonymous, to score the likelihood of four events happening in the next 18 months because of the DSA (see table below).

On average, the group was skeptical that the code of conduct and DSA would lead to breakthroughs in product interventions that give users power over the accuracy of their feeds. Daphne Keller, Director of the Program on Platform Regulation at Stanford, told me that "unfortunately the Commission's skepticism about Community Notes is a strong signal that user controls or user initiated corrections for problems will not be considered adequate risk mitigation. So that discourages platforms from prioritizing user controls."

Experts also doubt that the code will spur new interventions integrating fact checks into platforms comparable to the one Meta killed earlier this year.

They were far more optimistic about the DSA's transparency requirements leading to research breakthroughs, rating it on average 3.7 out of 5. And they were evenly split on whether a platform will get slapped with a big fine of at least 1% of their global turnover, with three experts scoring this a 1 or 2, and the rest going going for 3 (twice), 4, and 5. Keller told me that while she thinks a fine is likely "then there will be years of litigation. So I guess I'll give that a 3."

I'll be back in August 2026 to check in on these predictions. In the meantime, expect plenty more theater obfuscating what the DSA actually does and doesn't do.