🤥 Faked Up #21

California's law mandating disclosure of election deepfakes was struck down, Russian hackers targeted users of AI nudifiers, and Meta AI is probably not good enough to be dangerous

This newsletter is a ~7 minute read and includes 37 links.

HEADLINES

Character AI deleted a custom chatbot impersonating a murder victim. The UN estimates cyber scams cost victims in East and South East Asia as much as $37 billion. Meta removed more than 8,000 AI-generated celebrity investment scams since April. Instagram ran an ad falsely claiming a candidate for mayor in São Paulo did cocaine. The platform’s misinfo-matching algorithm is flagging false positive. TikTok is running ads for supplements that double up as North Korean propaganda. The blue checkmark may be coming to Google.

TOP STORIES

ONEROUS LABELING REQUIREMENTS

California’s election deepfakes law lasted all of two weeks. On Oct. 2, US District Judge John A. Mendez issued a preliminary injunction blocking the law on First Amendment grounds.

The law had been challenged by Christopher Kohls (“Mr Reagan”), the conservative creator behind the viral Kamala Harris parody ad.

From the decision:

AB 2839 does not pass constitutional scrutiny because the law does not use the least restrictive means available for advancing the State’s interest here. As Plaintiffs persuasively argue, counter speech is a less restrictive alternative to prohibiting videos such as those posted by Plaintiff, no matter how offensive or inappropriate someone may find them. ‘“Especially as to political speech, counter speech is the tried and true buffer and elixir,” not speech restriction.’

California’s law would have prohibited the dissemination of “materially deceptive content” of a candidate, elected official, elections officer or voting instrument if that content could harm the candidate’s reputation or falsely undermine confidence in the election. This is how the law defined “materially deceptive content:”

audio or visual media that is intentionally digitally created or modified, which includes, but is not limited to, deepfakes, such that the content would falsely appear to a reasonable person to be an authentic record of the content depicted in the media.

Protecting a candidate’s reputation certainly seems like a step too far. A visual recreation of well-founded allegations of corruption against (say!) a New York City mayor could harm their reputation for all the right reasons.

Still, it seems to me that the intent of the law was not to restrict speech as much as to mandate counter speech in the form of transparency labels.

The labels had to indicate that the content “has been manipulated” in a way that was easily readable and in a font no smaller than the largest font size used in the image or video. They would also have to appear for the entire duration of a manipulated video clip, or at standard frequencies in an audio clip.

Kohls complained that these “onerous labeling requirements” were impractical and the law put him “at immense financial risk.” The font size requirements probably did need to be reworked. As the plaintiff notes, a disclosure on his Harris parody video would have rendered the video unwatchable:

This seems like an easy fix. But the judge didn’t spend too much time on labeling. In fact, he said that part was probably OK:

The safe harbor carveouts of the statute attempt to implement labelling requirements, which if narrowly tailored enough, could pass constitutional muster.

Free speech experts agree. Here’s Alex Abdo, litigation director at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University:

The court was right to hold that the law’s core prohibition is unconstitutional. While the state has an interest in protecting the integrity of our elections, the First Amendment does not permit the government to outlaw speech about an election except in very narrow circumstances. The better way to address the risks that motivated the law would be to pass a labeling requirement, narrowly targeted at the uses of AI most likely to cause confusion or harm. A carefully drafted law along those lines would likely be constitutional.

It’s unclear whether such a carefully drafted law is coming in California, especially in time for the election. Governor Gavin Newsom’s spokesperson made it sound like the state will appeal, but I have seen no additional details in the following days.

Newsom may well be partly to blame for this debacle. It was silly of him to single out a parody ad and give Kohls the ground to cast himself as a free speech martyr (from the complaint: “Plaintiff responded to Governor Newsom’s threat of legal and regulatory action as anyone should against a bully—he punched back, posting another AI-generated, Harris-mocking video”).

What’s more, as I noted in FU#11, Kohls had disclosed the Harris video as parody and even, on YouTube, that he had used AI. Making this the centerpiece of a push against deceptive deepfakes invited the lawsuit that ultimately doomed the bill.

What’s left to see is whether this will inspire challenges to laws mandating deepfake disclosure in other states. While laws in Oregon and Washington appear to a non-lawyer like myself to be more narrowly scoped and possibly safe, California’s bill reads a lot like the one enacted in Indiana that recently made the news.

AI-GENERATED = WORSE

Speaking of labels, researchers are probing their effect on user’s perception of AI-generated content and the people disseminating it.

In a study on PNAS Nexus, two political scientists at the University of Zurich concluded that “labeling headlines as AI-generated reduced the perceived accuracy of the headlines and participants’ intention to share them, regardless of the headlines’ veracity (true vs. false) or origin (human- vs. AI-generated).” Still, the effect was relatively small: a 2.66 percentage point decrease for a “generated by AI” headline compared to a 9.33 percentage point decrease for content labeled as “false.”

In a separate report, the NYU’s Center on Technology Policy tested the effect of AI labels on political ads. They conclude that “in nearly all conditions, when subjects saw a label on an ad, they rated the candidate who made the ad as less appealing and less trustworthy.”

OH NO, BAD PEOPLE GOT HACKED :(

According to cybersecurity firm Silent Push, Russian hackers have set up a group of AI nudifiers to infect targets with malware. The company told 404 Media that they believe the notorious threat group Fin7 may be behind the websites, which look just like any other AI undressing service. When you go to upload the image you want to undress, however, the sites open up a link to “download a trial” that’s actually an infostealer.

META’S BLENDED UNREALITY

I’ve previously written about the Reimagine feature on Pixel 9 that lets you dramatically and realistically alter images within seconds and with few guardrails.

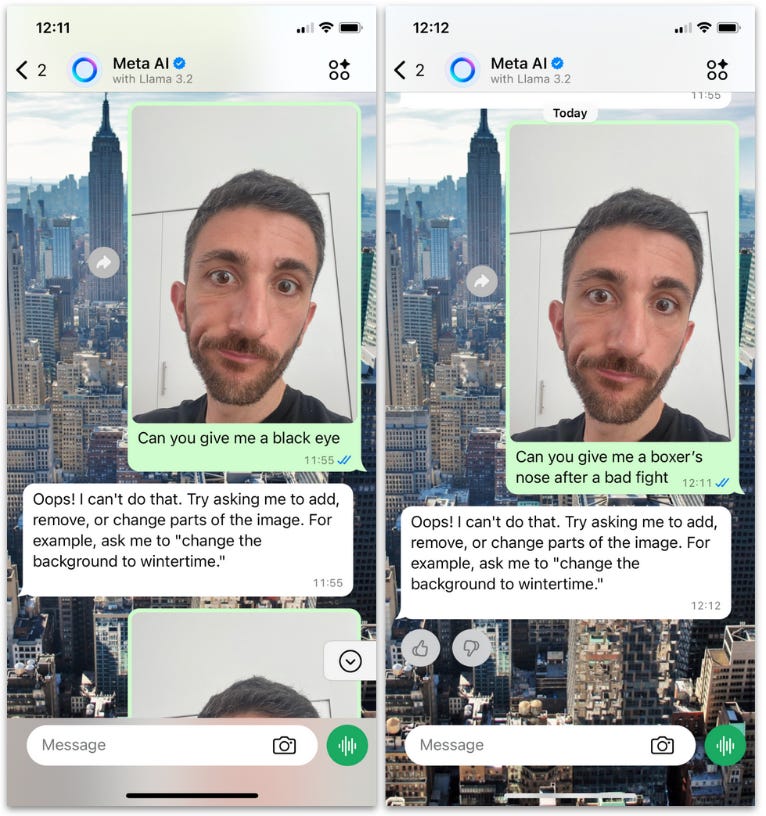

But Google isn’t alone; Meta AI’s image manipulation product works in a similar way. Accessible to everyone with an Instagram or WhatsApp account, the chatbot balked at obviously sensitive keywords but with minimal rephrasing provided me with an image that could be used to spread false narratives of voter fraud at a NYC voting location.

The good news is that Meta does add a visible label, though that can be easily cropped out. It is also relatively timid about editing people’s faces in a potentially problematic manner.

It is also…not terribly good? Its fires, for one, are cartoonish and far less believable than those you can get on the Pixel, for example.

Still, WhatsApp has over 2 billion monthly active users. That’s a far bigger penetration than the Pixel 9 and therefore a likelier source of deceptive deepfakes in the coming months.

ASYMMETRY IN, ASYMMETRY OUT

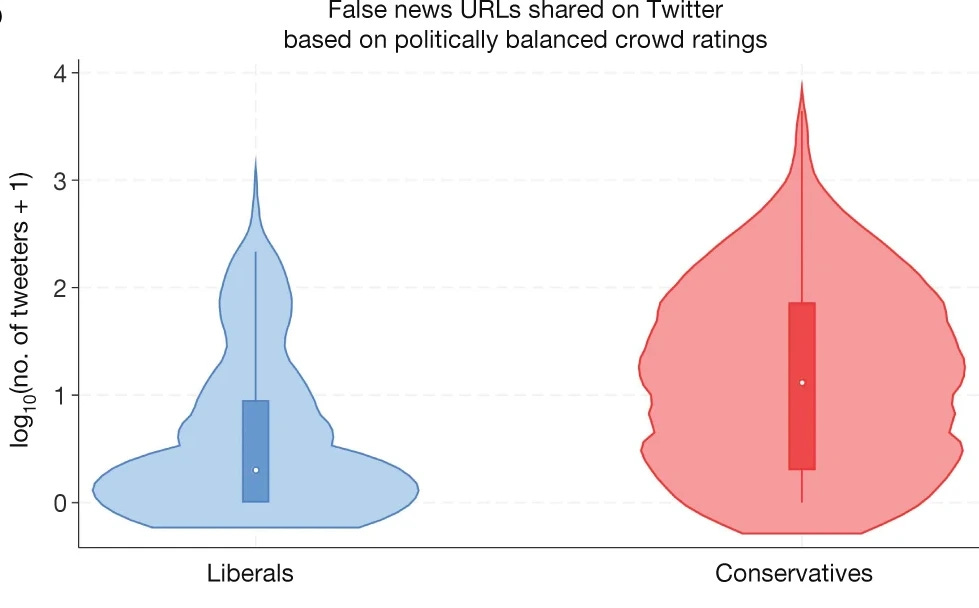

A study on Nature argues that politically asymmetrical suspensions of social media users may be explainable by an asymmetrical sharing of misinformation by those accounts, rather than by platform bias.

The researchers found that that Twitter “accounts that had shared #Trump2020 during the election were 4.4 times more likely to have been subsequently suspended than those that shared #VoteBidenHarris2020.”

This could have been for a range of reasons, including bot activity or incitement to violence. Still, the pro-Trump accounts were also far more likely to share links to low-quality news sites that may have been flagged for misinformation. Crucially, this discrepancy held even when the news sites were rated by a balanced sample of laypeople rather than by referring to existing lists compiled by fact-checkers and other media monitors.

The researchers also found that this disparity largely held on Facebook, in survey experiments, and across 16 different countries.

AI PEACOCKING

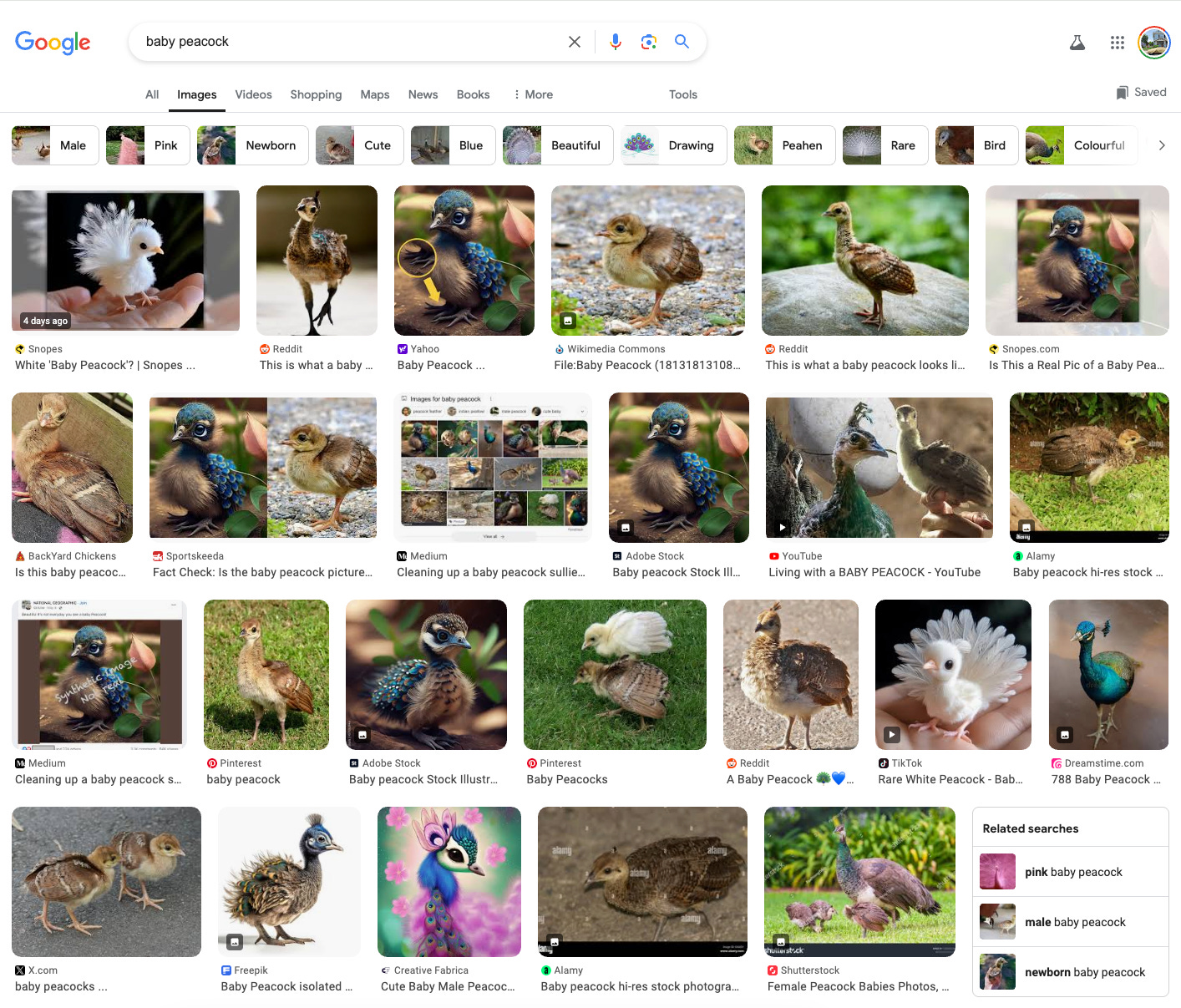

Google Image results for [baby peacock] have been flooded by AI-generated images that do not actually depict what a peachick actually looks like. (A young peafowl is a peachick. Feel free to use this knowledge with 6 year olds in your life; I certainly plan to.)

This is a known issue — Emily Bender wrote about this issue in a perceptive piece more than a year ago — but has resurfaced because of crummy viral content on TikTok and X. I should note that several of these top images do then lead to fact checks of the AI images, but that’s likely a click many people won’t be making.

NOTED

- Truth Social Users Are Losing Ridiculous Sums of Money to Scams (Gizmodo)

- Some online conspiracy-spreaders don’t even believe the lies they’re spewing (The Conversation)

- Internal Emails Reveal How Hate Overwhelmed Springfield After Trump's Lies About Haitian Immigrants (404 Media)

- India’s Generative AI Election Pilot Shows Artificial Intelligence in Campaigns is Here to Stay (Center for Media Engagement)

- Social media fuel pro-Okinawa independence disinformation blitz (Nikkei Asia)

- Views stay divided on POFMA five years on, but has it helped in tackling fake news? (Channel News Asia Today)

- The racist AI deepfake that fooled and divided a community (BBC)

- What’s Hiding Under the Kilt? Iranian Trolls for Scottish Independence (Clemson Media Forensics Hub)

Member discussion