🤥 Faked Up #17

Brazil's disinformation takedowns lack transparency, RT covertly paid right-wing influencers $400K/month, and Meta ran hundreds more ads for deepfake nudifiers

This newsletter is a ~8 minute read and includes 81 links. I ❤️ to hear from readers: please leave comments or reach out via email.

Last week’s Faked Up analysis of AI nudifier ads on Meta was featured on The Washington Post! More about that further down.

THIS WEEK IN FAKES

The US Department of Justice seized 32 domains associated with the Doppelganger influence operation. Google’s Reimagine is a ticking misinformation bomb (see also FU#15). An Australian MP made deepfakes of the country’s prime minister to prove a point. Nikki Haley released a grudge. Police in Springfield, Ohio, said there was no evidence to back up a Facebook post claiming immigrants were eating local pets (to little avail. Very little avail). Musk may get summoned by British MPs about hateful misinformation. Plus: can you beat my 9/10 score at this deepfake-spotting quiz?

TOP STORIES

DISINFORMATION AND BRAZIL’S X-IT

Brazil’s ban on X has been widely framed as a disinformation issue.

In the immediate sense, that’s not quite right. As the think tank InternetLab put it in an emailed brief, the ban follows X’s non compliance with a legal order related to the “intimidation and exposure of law enforcement officers” connected to the Supreme Court’s inquiry into the Jan. 8 attacks.

At the same time, the ban is the end result of five years of judicial actions targeting disinformation about the Supreme Court and the electoral process.

To try and understand how online disinformation removals work in Brazil, I consulted fact-checkers Cristina Tardáguila and Tai Nalon, tech law scholars Carlos Affonso de Souza and Francisco Brito Cruz, and law student Vinicius Aquini Goncalves.

The legal grounds

The 2014 Marco Civil da Internet, Brazil’s Internet Bill of Rights, makes internet providers liable for harmful content on their platforms if they don’t remove it following a court order. As Souza told me, the law is “not a guidance … It is binding, so judges need to apply that.” At the same time, he thinks it is “in dire need of some updates, especially concerning issues of content moderation.”

A legislative attempt to provide this update came in 2020, with the “fake news” bill (PL/2630). The draft bill would have defined several terms, including inauthentic accounts, fact-checking, and disinformation (content that is “verifiable, unequivocally false or misleading, out of context, manipulated or forged, with the potential to cause individual or collective damage”).

For a variety of reasons, including real flaws in scope, the fake news bill never passed, leaving digital disinformation undefined and unregulated by Brazilian legislators.

The judicial branch filled this void. In 2019, the Supreme Court opened an inquiry into online false news about the institution and its members. According to legal scholars Emilio Peluso Neder Meyer and Thomas Bustamante, this relied on an “unusual interpretation” of the court’s internal rules whereby because it can “investigate crimes committed inside the tribunal’s facilities,” it can investigate crimes on the internet.

Even as this inquiry pursued what several viewed as legitimate harms, it has also been described to me as “highly unusual” and “very heterodox.”

Another key element of the online anti-disinformation puzzle is the October 2022 resolution by the Supreme Electoral Court (TSE). This gave the TSE president the unilateral power to request takedown of disinformation identical to that previously removed under previous court orders and the ability to fine platforms ~$20K for every hour the content stays online after the second hour of notification.

In February of this year — with local elections coming up in October — the TSE also banned the use of deepfakes in political campaigns.

The takedowns

The first thing to note is that takedown requests made by the Supreme Court and the TSE are confidential. “The press can’t see anything; it’s very opaque,” Tardáguila says.

What little information we have on individual takedowns is what is being shared by recipients of the orders, like X. Brito Cruz says even that information is incomplete because it doesn’t contain the full reasoning of the court.

In addition, decisions are often taken at the account level rather than at the individual URL level (Aos Fatos published an overview of some of the targeted X accounts here.)

Back in April, Lupa reviewed social media content related to 37 TSE takedown requests released by X for a report by the US House Judiciary Committee. To date, I think it is the most comprehensive independent analysis of the merit of individual takedowns that is available. Together with what is being selectively disclosed in the Alexandre Files, this gives us a very partial picture of the content: Debunked theories about voter fraud, misleading attacks against President Lula and high-voltage criticism of the Supreme Court. Clearly, not all of this is disinformation; but then again, not all of it was actioned on those grounds.

Other transparency reports by targeted platforms provide a sense of the scale of requests.

TikTok claims to have removed 222 links in response to 90 court orders in 2022, the year of the most recent presidential election. This pales in comparison with the 66,000 videos the platform claims to have deleted of its own volition for violating its electoral disinformation policies. However, without data on the relative reach of these two sets, these figures are not quite fair to compare.

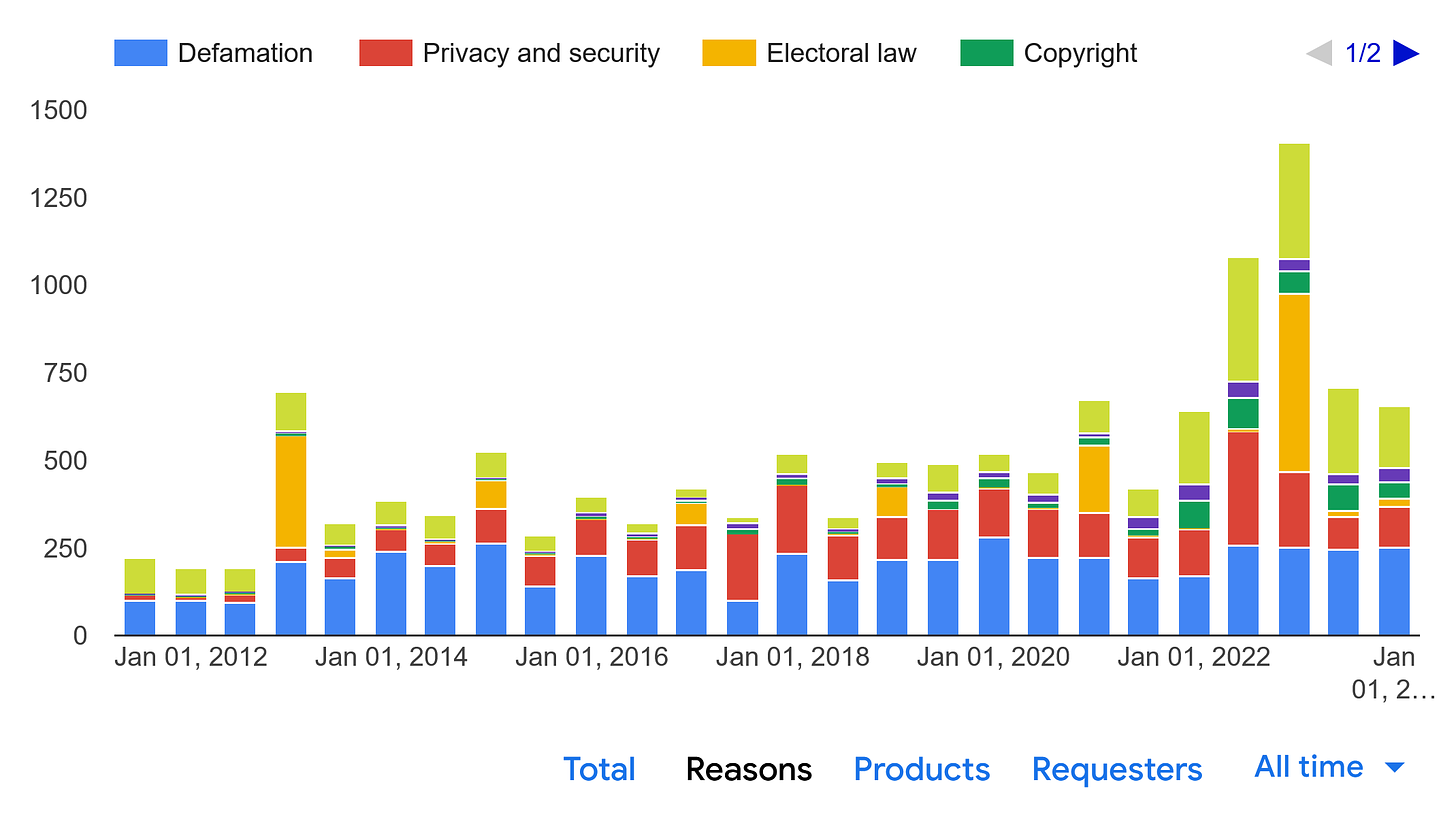

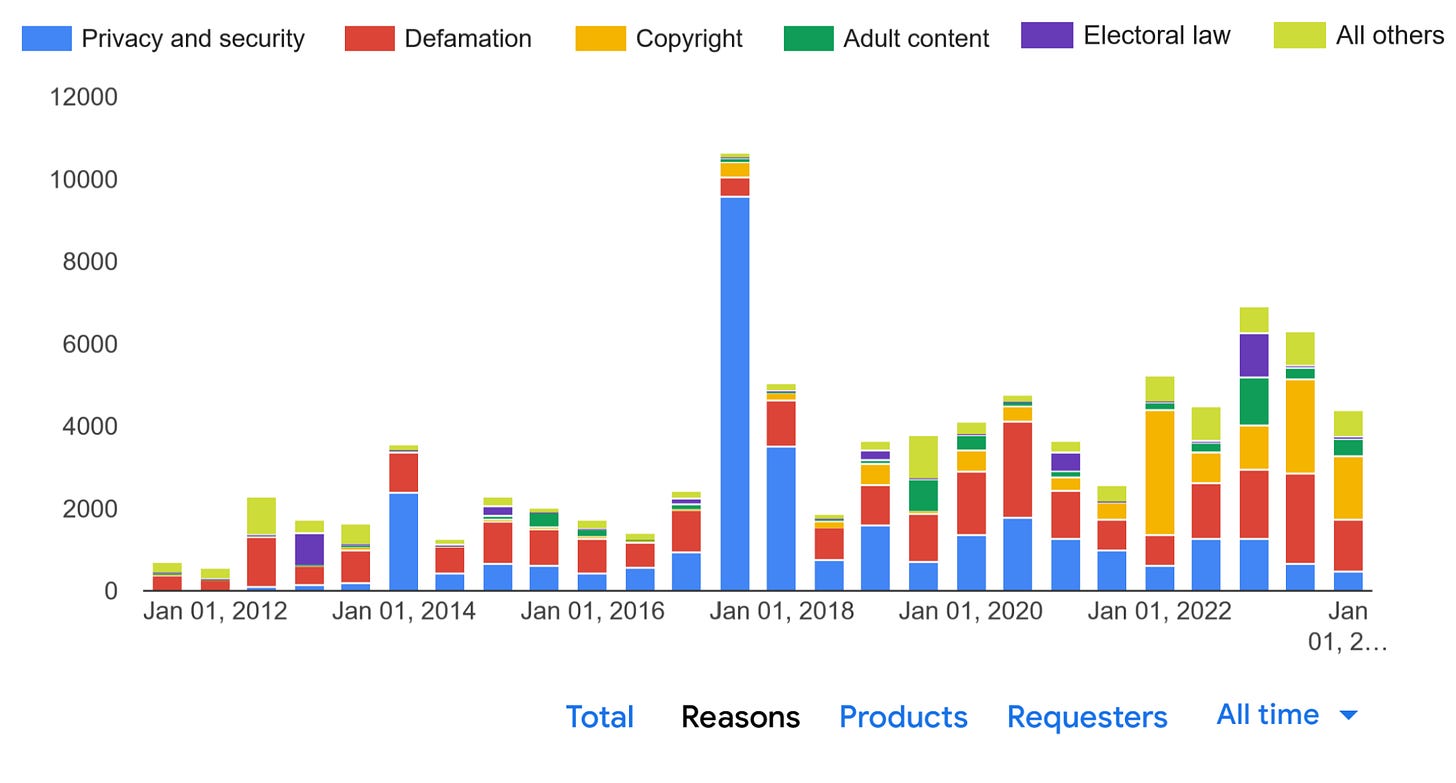

Google’s transparency report is also helpful in that it clusters takedowns by reason. Electoral law was the grounds for 36% of removal requests in the six months to December 2022; that was figure was just 3% in H2 2023.

Looking at the data by number of items removed, the overall share of electoral takedowns is reduced but nontrivial — Google reported 1,043 items removed in the second half of 2022. But given that some disinformation requests may fall under the defamation category, that, too, is an incomplete picture.

Aos Fatos, for one, is trying to compensate by tracking disinformation and AI-related keywords in judicial decisions to track how the deepfake ban is being applied by regional electoral courts (across all platforms and the open web, not just X). Nalon says they are building up an automated system with a view to better monitoring the 2026 presidential election.

But at least at this stage, the information shared by Brazil’s courts and gleaned from platform transparency reports is scarce and scattered. This makes it very hard to make an honest assessment of the scale and fairness of Brazil’s anti-disinformation decisions.

As Brito Cruz told me, “the lack of transparency is a concern for all of us.”

RT WAS NOT IN IT FOR THE ROI

The US Department of Justice claims that Konstantyin Kalashnikov and Elena Afanasyieva, two employees of Russian state-controlled media outlet RT, channeled nearly $10 million to “covertly finance and direct a Tennessee-based online content creation company.” The company has been identified as Tenet Media, run by far-right Canadian influencer Lauren Chen and her husband.

In turn, the indictment alleges, Tenet paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to sign American right-wing influencers including Benny Johnson, Dave Rubin and Tim Pool (each claimed victimhood).

The indictment is a riveting read and CBS, NBC and WaPo have done a great job covering the fallout. But if you take only three things out of it, let it be these:

- The DOJ documents indicate that RT wasn’t looking for a financial return on investment. Before signing them on, Chen warned Kalashnikov that Pool and Rubin “would not be profitable to employ” but the RT employee greenlit the proposal anyway (Pool has since claimed that $100,000 per video is “market value.”). Still, the influencers bought the RT operation an audience: in less than a year, Tenet Media had collected 330K subscribers and 16M views on YouTube.1

- The content was probably in line with what the influencers were posting already — Wired scraped Tenet’s videos before YouTube took them down and analyzed frequent terms. But at least once, one of the influencers appears to have accepted an editorial recommendation to cover the Crocus City Hall terrorist attack “from the Ukraine-US angle”.

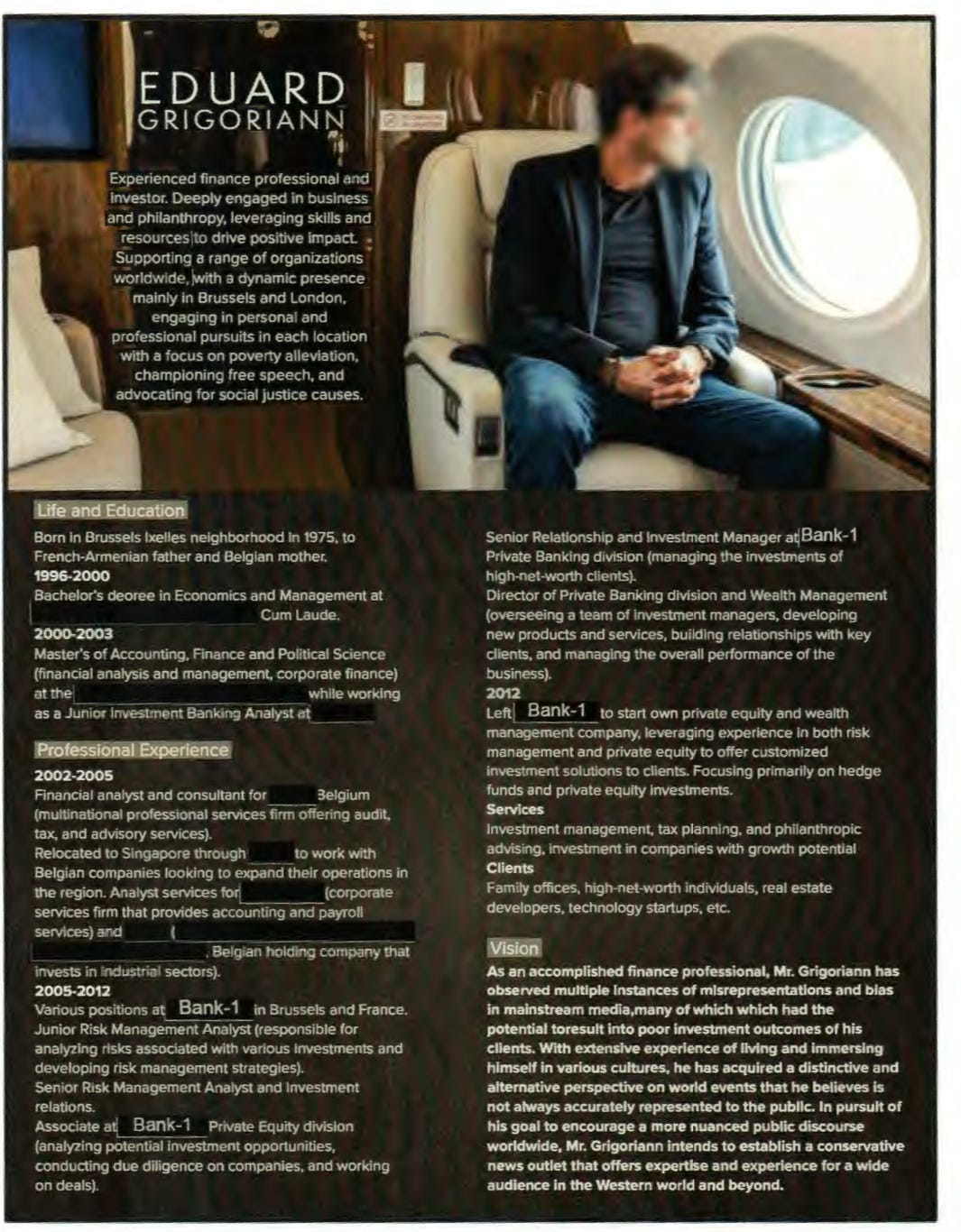

- Not a lot of due diligence appears to have gone into these deals. Two of the right-wing influencers were content with the CV below as evidence of the existence of a well-heeled funder behind Tenet Media who could afford their honoraria. No other online footprint was available for Eduard Grigoriann — and even Tenet’s founders kept misspelling his surname in communications.

The indictment also says that Tenet Media was one of “multiple RT covert distribution channels in the United States.” It remains to be seen whether the DOJ will reveal more active deceptive creators or whether the others have already been identified by social networks.

CRUSHMATE CRUSHING IT ON META

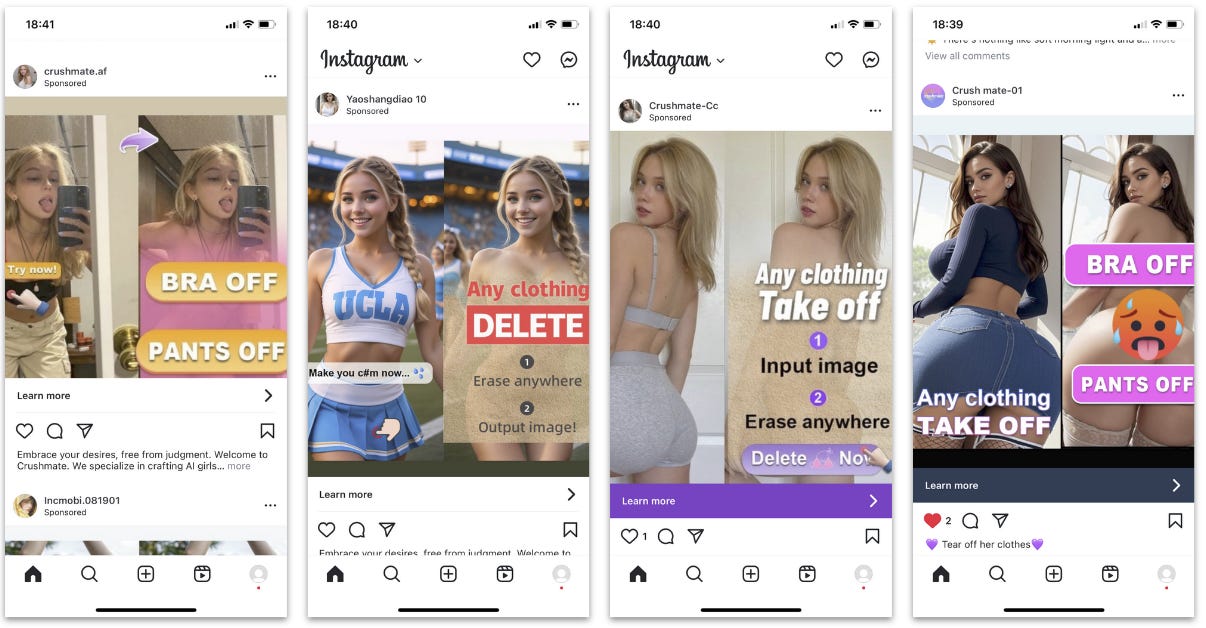

Last week, I wrote about several “AI undressers” running more than 200 ads on Meta’s platforms.

The good news is that Meta removed most of the ads following my article and Google blocked one of the related apps (Apple does not return my emails).

The bad news is that this weekend one of the undressers was still able to run ads from a range of other Facebook and Instagram pages. On Sunday, I collected 377 ads from 16 pages tied to this network.2 All of them pointed to the same service, called Crushmate. I reached out to Meta for comment and by Tuesday night they had taken down 15 of the 16 pages. A spokesperson told me that “we’re continuing to remove the ads and take action against the accounts breaking our rules.”

For as long as they lasted, these ads appeared to be paying off for Crushmate.

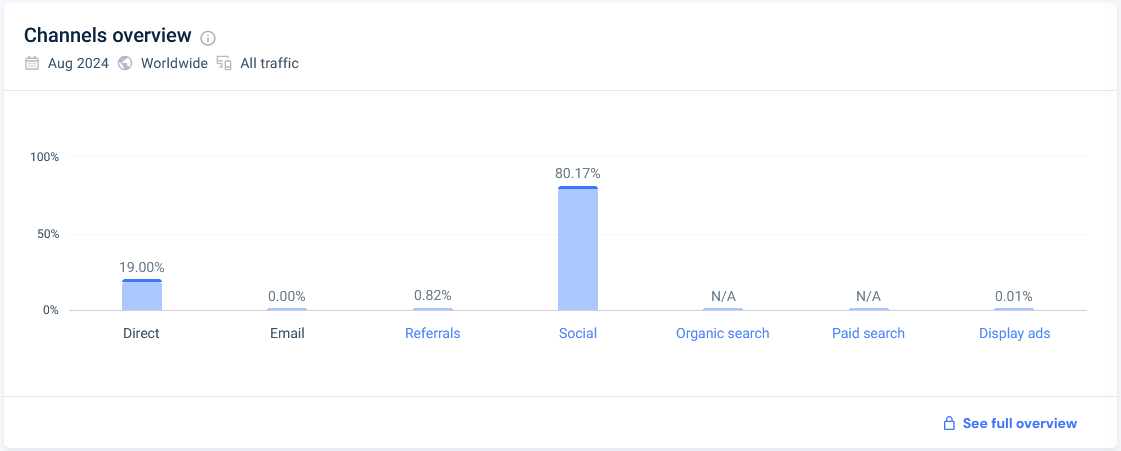

According to SimilarWeb, the main site in the network, crushmate[.]club, got 80% of its 130K visitors from social media in August.

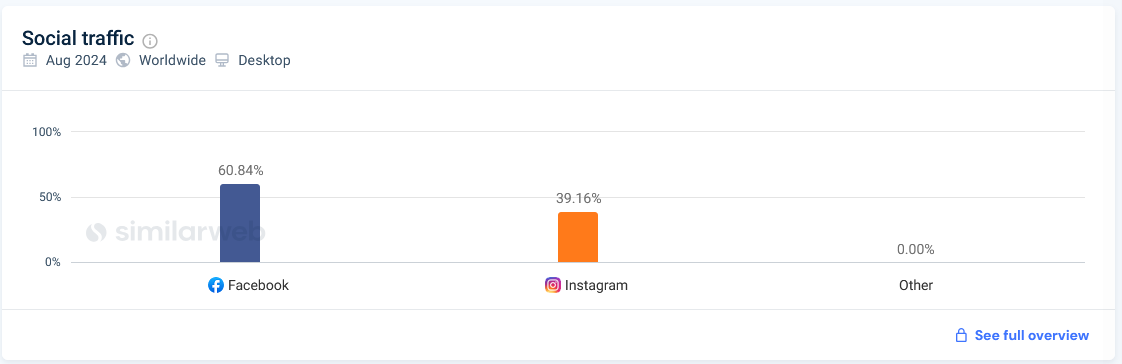

The entirety of that social media traffic came from Facebook and Instagram:

DISRUPTIVE EDITING

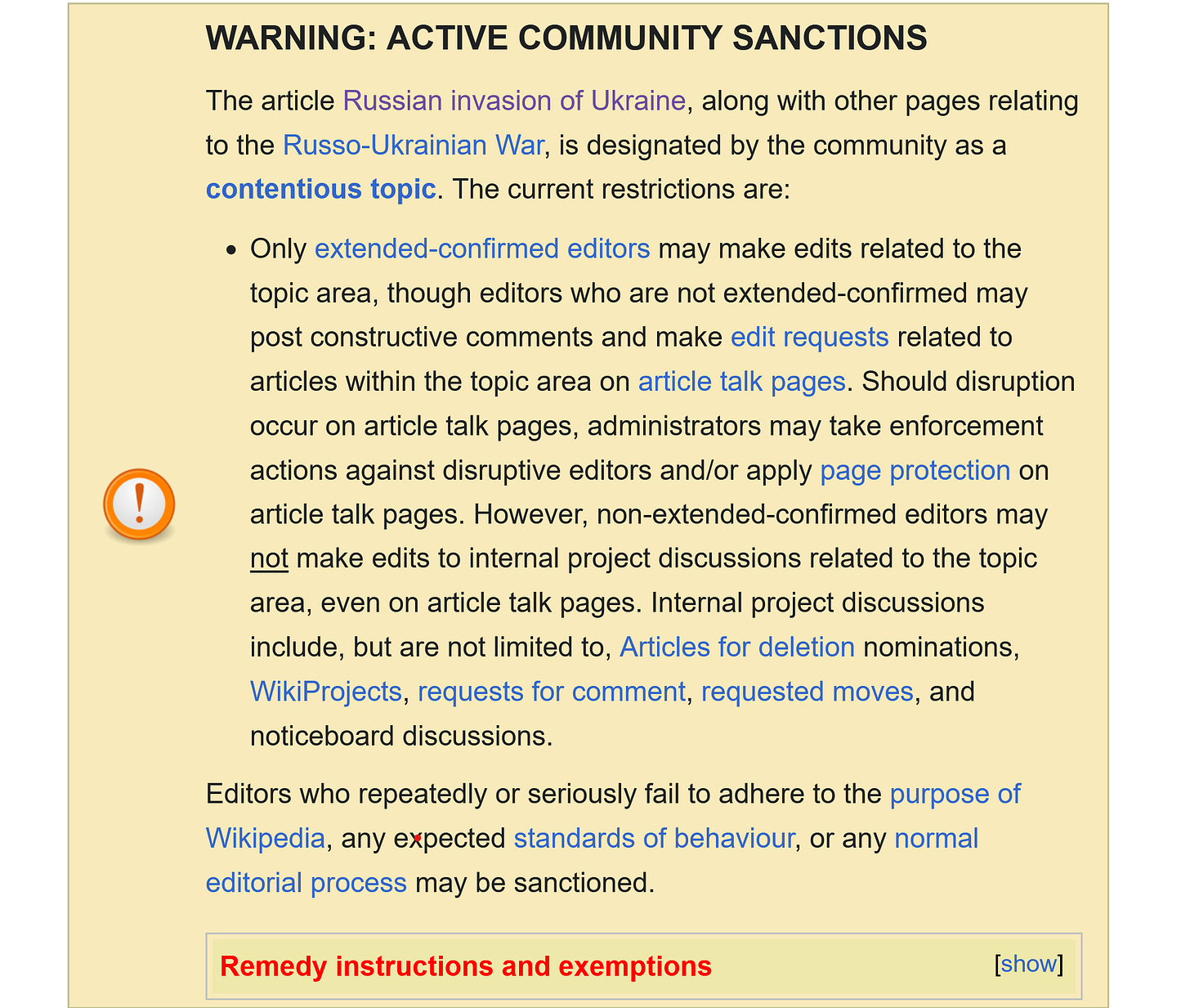

13 expert Wikipedia editors told three researchers at the University of Michigan that they “did not perceive there to be clear evidence of a state-backed information operation,” in the Wikipedia pages about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, ”they agreed that war-related articles experienced high levels of disruptive editing from both Russia-aligned and Ukraine-aligned accounts.”

The Wikipedians also warned that while the main page on the conflict “was fairly neutral,” there were thousands of peripheral pages not on watch lists whose quality was more likely to have been affected by partisan editing.

A ROADMAP FOR LABELING AI

I appreciated this analysis and roadmap for the future of AI labeling by Claire Leibowicz at the Partnership on AI.

I especially liked how she called out that legislators drafting labeling requirements are taking the “politically pragmatic” path by focusing on “the method of manipulation (i.e, technical descriptions of the use of AI) as a proxy for the normative meaning of the manipulation.”

This, Leibowicz notes, is an acceptable but inadequate proxy: “Just because something was made with AI does not mean it is misleading; and just because something is not made with AI does not mean it is necessarily accurate.”

I DON’T TRUST YOU BUT I BELIEVE YOU

Important takeaway in this study on Nature Human Behavior for those designing anti-misinformation interventions in online spaces.

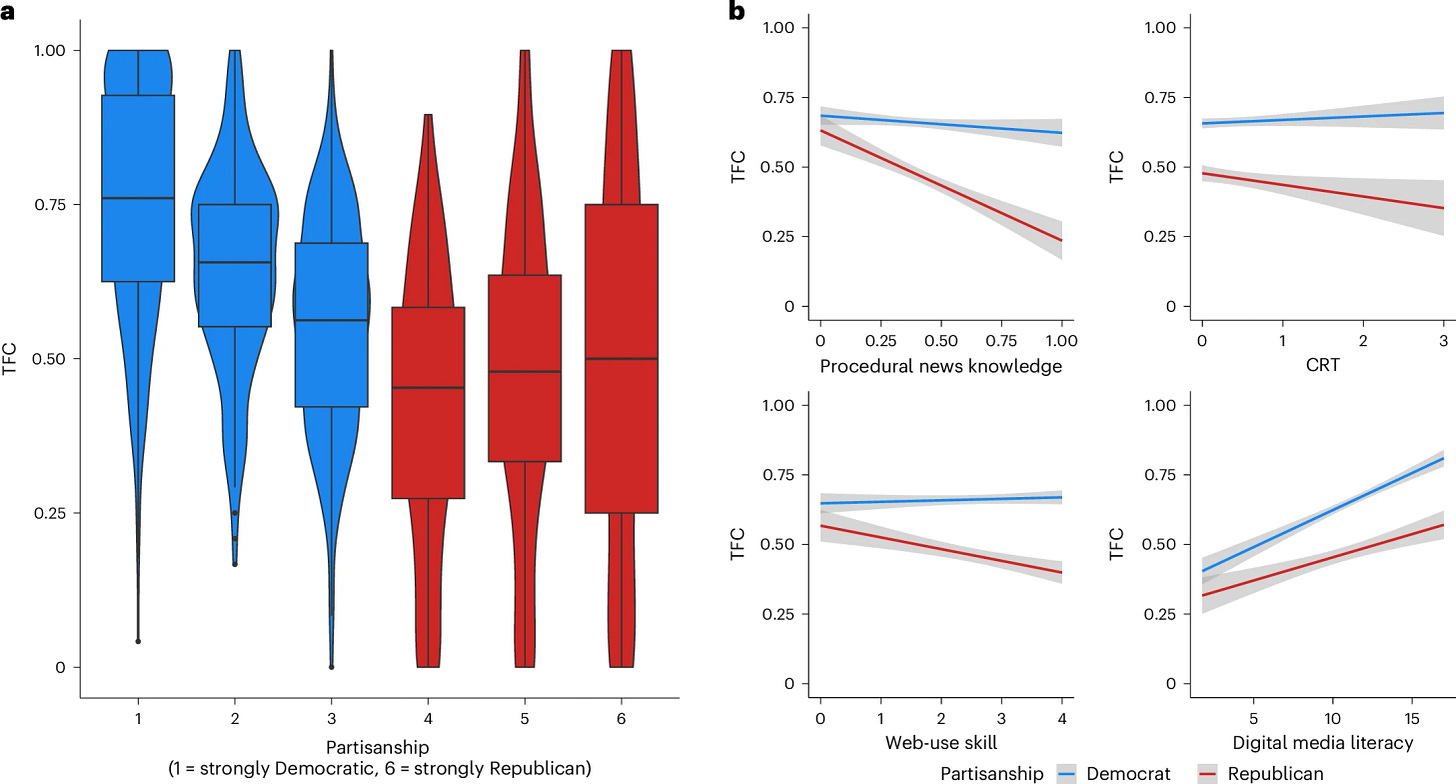

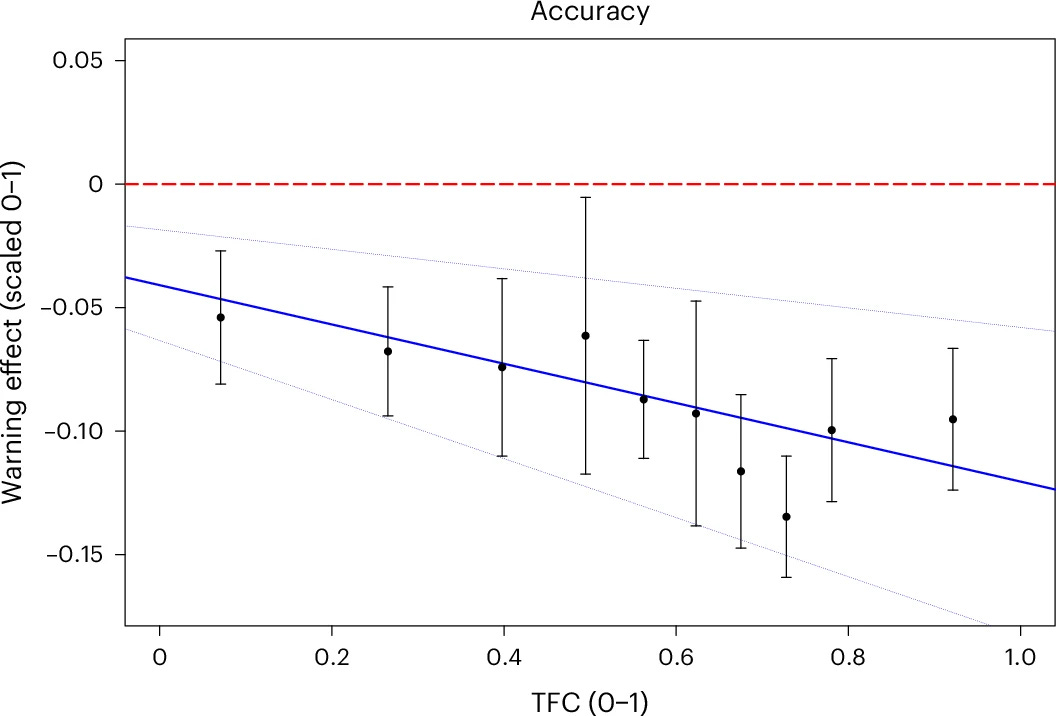

Fact check warning labels reduce Americans’ propensity to believe or share false news despite differential trust in fact-checkers across political persuasions. As you can see in this chart, trust in fact-checkers is higher with Democratic voters:

But even when trust in fact-checkers is lowest (left on the x-axis below), fact checks still reduced the perceived accuracy of the labeled false news.

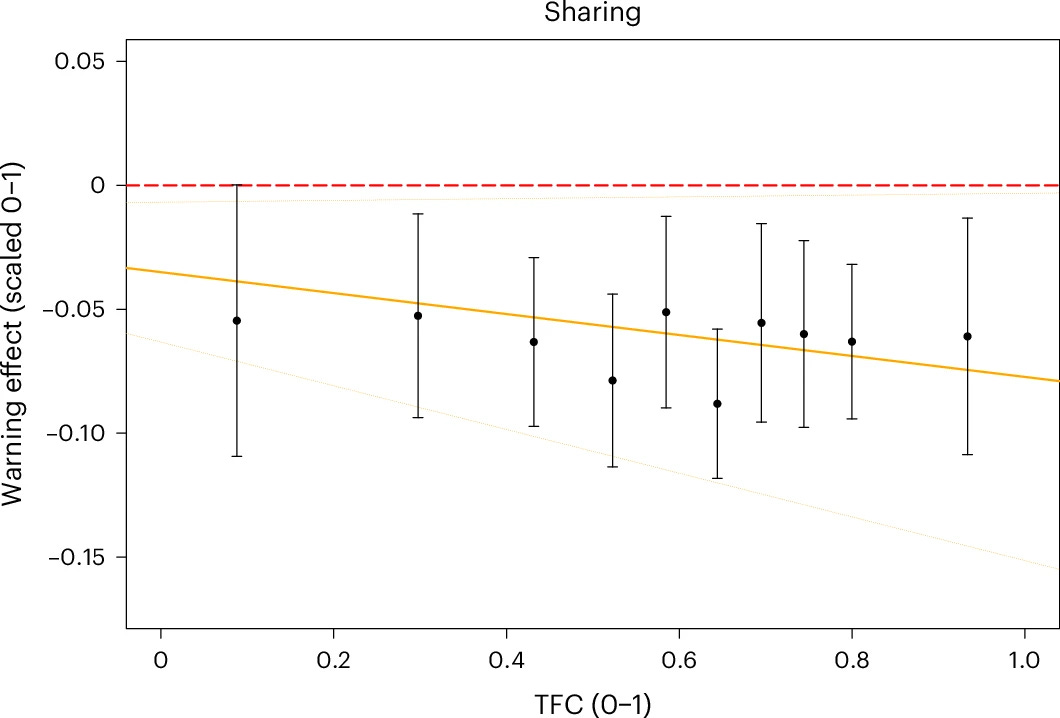

The chart looks the same for sharing intentions. Even though higher trust does lead on average to a higher reduction in sharing labeled false news, the effect is consistent across the board.

NOTED

- Reality Check Commentary: I Unintentionally Boosted an AI “Content Farm” Business. I Don’t Regret It. (NewsGuard)

- The New Recruitment Challenge: Filtering AI-Crafted Résumés (WSJ)

- Human detection of political speech deepfakes across transcripts, audio, and video (Nature — see also author’s thread)

- AI worse than humans in every way at summarising information, government trial finds (Crikey)

- Conspiradores criam mentira para relacionar Bill Gates, Mpox e ‘chemtrails’ (Aos Fatos)

- How influencers and algorithms mobilize propaganda — and distort reality (Nature)

- IPhone 16 is all about Apple Intelligence. Previews show it can be kind of dumb. (The Washington Post)

- Elon Musk’s misleading election claims reach millions and alarm election officials (The Washington Post)

- Scam Sites at Scale: LLMs Fueling a GenAI Criminal Revolution (Netcraft)

ONE NICE THING

OK folks, I’ve heard from my in-house focus group that the “Faked Map” wasn’t working. I still don’t want to send you a bunch of depressing updates about online fakery and then sign off, so I’ll use this spot to share one nice thing I see online. Like this NASA tool to spell anything with satellite imagery.3

PS. Did you secretly love Faked Map? Email me so I can use your testimonial in one of those classic I told you so moments that buttress a happy marriage.

1 Whereas YouTube and TikTok terminated Tenet’s profiles, those on Facebook, Instagram, Rumble and X were still online at the time of writing.

2 Here’s the full list:

3 OK, because I have a problem I tested whether the tool has any moderation features. Looks like NASA has a blocklist for common swearwords, but that’s about it.

Member discussion