🤥 Faked Up #1

Hi, folks.

Thank you for signing up before the first issue of Faked Up was even out. I will work hard to be worthy of your confidence. For complaints, story ideas or tips…email me.

This newsletter is a ~6-minute read and contains 55 links

Top Stories

UNDOING UNDRESSERS

Google announced on May 1 that it would ban all ads for AI-generated porn, even if there is no nudity in the ad itself.

This is a welcome move. Still, there is plenty of work left to do.

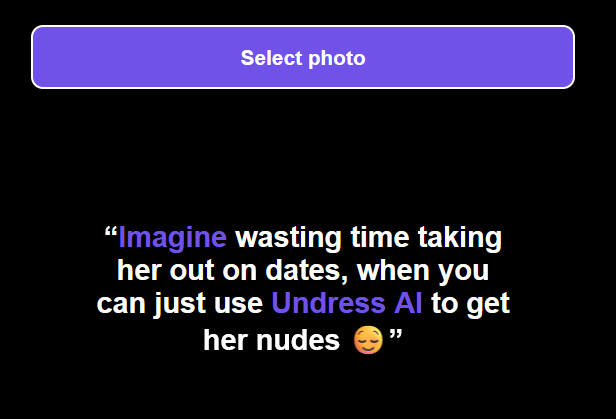

Of particular concern are “undressers” or “nudifiers” — apps that take a real picture of a person wearing clothes and turn it into a nude. While deepfake porn generators can in principle have legitimate use cases, nudifiers are tools of harassment used to target high school girls in Brazil, Spain and at least two US states. Here’s how one of these website markets itself explicitly for non consensual purposes:

Nudifiers leverage a range of platforms for their operations. They use [cw: explicit content] Telegram for customer service and Twitter for marketing. They offer apps for Apple and Android and sign-in through Discord or Google.

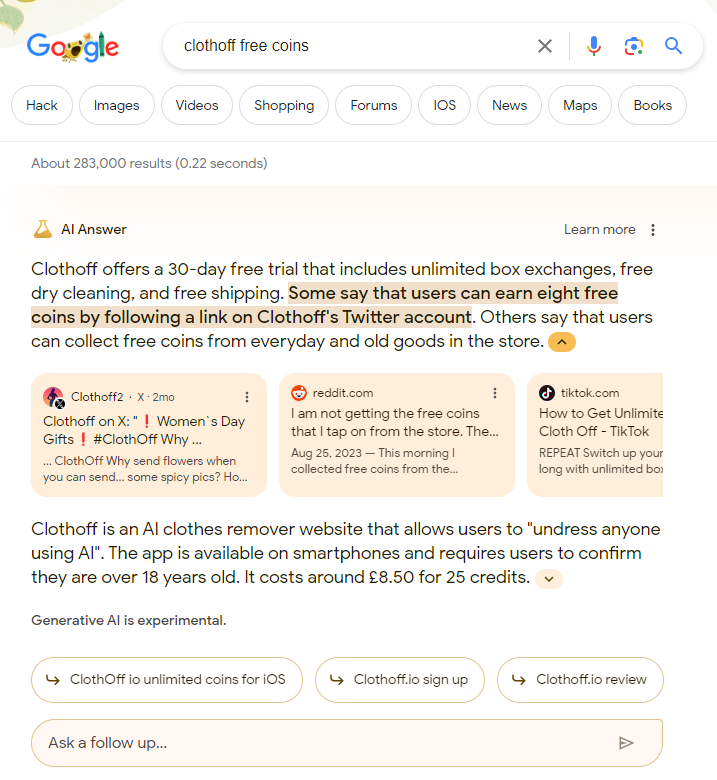

And they reach millions through search engines. According to SimilarWeb, approximately 1 million of clothoff[.]io’s 4.4 million monthly visits originated from organic search. While it is expected behavior that searching for the name of a legal website returns a basic link to the website, undressers also trigger more immersive features that are typically verboten for harmful content.

Take Google’s result for [clothoff free coins], which highlights a coin giveaway in its new Search Generative Experience.

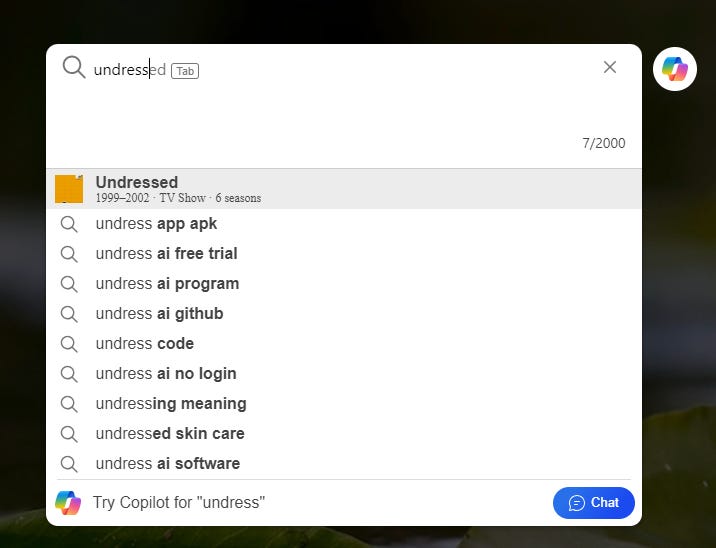

Results on other search engines are similarly structured. Bing provides suggestions when typing in [undress] that expose users to nudifier content they may not have even been searching for:

Governments are moving slowly. On April 30, Australia’s government announced it would pursue a ban on "the creation and non-consensual distribution of deepfake pornography." The UK government has similar plans. In the US, a bill drafted last year has yet to make it out of subcommittee.

Content moderation is typically bedeviled by hard trade-offs. This is not such a case. Stamping out nudifiers should be a moral priority for the architects of the generative AI revolution and their overseers.

PROBABILISTIC DETECTION

OpenAI announced on May 7 that it would share with a small group of disinformation researchers a tool it built to detect deepfakes created by its users. The company claims the tool is 98.8% accurate on images created with DALL-E 3, but that precision goes down if these images have been altered (e.g. resized, cropped, etc).

I am not a technical expert of how deepfake detectors work, but as a close follower of their results, I am skeptical. OpenAI itself deprecated its text detector last year because of a “low rate of accuracy.” This is not to say that detection shouldn’t be pursued. But, as with watermarking — which OpenAI also doubled down on by joining C2PA — these tools are only ever going to return a likelihood that something is deepfaked, not a certainty. I am worried that this nuance will be lost on the general public and weaponized by bad faith actors.

More and more, I think that confidence on the open web will have to be built at the actor level — trust will come not from what you see, but who has shared it.

AI AND CAMPAIGNS

Rest of World reports that Indian politicians will have spent $50 million in AI-generated campaign material by the end of this election window. Their suppliers are mostly small agencies that build tools allowing voters to generate fake selfies with their political idol or create videos “resurrecting” dead figures to endorse current candidates.

Obviously, this content can also be used for misinformation. Over the past year, deceptive deepfakes have targeted Indian, Slovakian, UK and US political candidates.

According to a recent survey by McAfee, about one in five respondents in both India and the US “said they recently came across a political deepfake they later discovered to be fake.” I’d venture this is likely inflated by respondents who understood “deepfake” to mean merely “misleading” — a semantic merger encouraged by Indian politicos, according to BOOM — but it is a notable proportion notwithstanding.

It is in this environment that nonprofits Demos and Full Fact have published a smart open letter calling on UK political parties to set the following guardrails on gen AI use:

Not using generative AI tools to produce materially misleading audio or visual content that might convince voters into believing something is true when it is not;Clearly labelling where generative AI is used to produce audio or visual content in a non-trivial way;Not amplifying materially misleading AI-generated content and, where appropriate and a significant risk, to be a responsible actor in calling this out in such a way that does not contribute toward further amplifying this content;Ensuring that party staff, members, volunteers and supporters are given clear guidelines for the use of generative AI in election campaigning.

DATA TO DETER DISINFORMATION

This article in The Economist about research on disinformation is worth reading in full. For one, it contains a great summary of the International Panel on the Information Environment’s 2023 review of countermeasures to digital disinformation:

[The IPIE] drew up a list of 11 categories of proposed countermeasures, based on a meta-analysis of 588 peer-reviewed studies, and evaluated the evidence for their effectiveness. The measures include: blocking or labelling specific users or posts on digital platforms; providing media-literacy education (such as pre-bunking) to enable people to identify misinformation and disinformation; tightening verification requirements on digital platforms; supporting fact-checking organisations and other publishers of corrective information; and so on.

The IPIE analysis found that only four of the 11 countermeasures were widely endorsed in the research literature: content labelling (such as adding tags to accounts or items of content to flag that they are disputed); corrective information (ie, fact-checking and debunking); content moderation (downranking or removing content, and suspending or blocking accounts); and media literacy (educating people to identify deceptive content, for example through pre-bunking). Of these various approaches, the evidence was strongest for content labelling and corrective information.

The article then notes that “a big obstacle for researchers is the lack of access to data,” often due to platforms’ unwillingness to share it.

This is a familiar qualm (I wrote about it 7 years ago) but FWIW, my sense is part of the problem is platforms don’t necessarily keep this data in a particularly organized manner. That is likely to improve thanks to the EU Digital Services Act, which requires platforms to report on “systemic risks” — including disinformation about elections and health — and share data with researchers.

“But so far, few have been successful” accessing the data, reports The Economist:

Jakob Ohme, a researcher at the Weizenbaum Institute for Networked Society, has been collecting information from colleagues on the outcomes of their requests. Of roughly 21 researchers he knows of who have submitted proposals, only four have received data.

And then there’s America, where “efforts to fight disinformation have become caught up in the country’s dysfunctional politics.” Hmm, I wonder what that’s about.

IS CHINA BAD AT DISINFO?

Experts told Wired that China’s influence operations are still unsophisticated and don’t “stick” — for now. This echoes findings by Google that the “overwhelming majority” of Chinese operations detected in 2022 “never reached a real audience.” Still, there is enough volume for the occasional breakthrough, as with a misleading tweet about a US neo-Nazi which got retweeted by Alex Jones. And, as an extensive new ASPI report found, China’s propaganda units are building deep ties with tech firms in order “gain insights into target audiences for its information campaigns.”

THE BUILDERS V THE FIXERS

On The Atlantic, Charlie Warzel published a must-read profile of ElevenLabs, the startup worth $1 billion behind the $1 Biden deepfake robocall. Warzel’s closing paragraph is a whole vibe:

Turns out, you can travel across the world, meet the people building the future, find them to be kind and introspective, ask them all of your questions, and still experience a profound sense of disorientation about this new technological frontier. Disorientation. That’s the main sense of this era—that something is looming just over the horizon, but you can’t see it. You can only feel the pit in your stomach. People build because they can. The rest of us are forced to adapt.

Headlines

- Unauthorized AI Voice Clones of Taylor Swift Face Removal From TikTok (Bloomberg)

- Facebook’s deep-fake ASX video scam (The Australian)

- Malacañang flags deepfake audio of Marcos ordering military attack (Rappler)

- Do You Like These AI Images of Dying, Mutilated Children? Facebook Algorithm Wonders (404 Media)

- Generative AI is already helping fact-checkers. But it’s proving less useful in small languages and outside the West (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism)

- Scammers use artificial intelligence to impersonate Sunshine Coast mayor as experts warn of video call cybercrime tactic (ABC News)

- Moldova fights to free itself from Russia’s AI-powered disinformation machine (Politico)

- Deepfakes of your dead loved ones are a booming Chinese business (MIT Technology Review)

Before you go

This app creates an “AI audience” that hypes you on live streams; dubious dudes claim to use it to pick up girls.

Super stars have moms just like ours.

AI “priest” Father Justin gets defrocked for his views on Gatorade and baptisms.

Did you enjoy this issue? Consider sharing it with a friend or two. They get to find out about a newsletter that might be useful to them — and you get up to 12 months of free access to Faked Up.

Member discussion